- In The Dreamhouse Barbie

- Who Is The Woman In The Dreamhouse Machado

- In The Dream House Book Carmen Maria Machado

- Life In The Dreamhouse

The new European data protection law requires us to inform you of the following before you use our website:

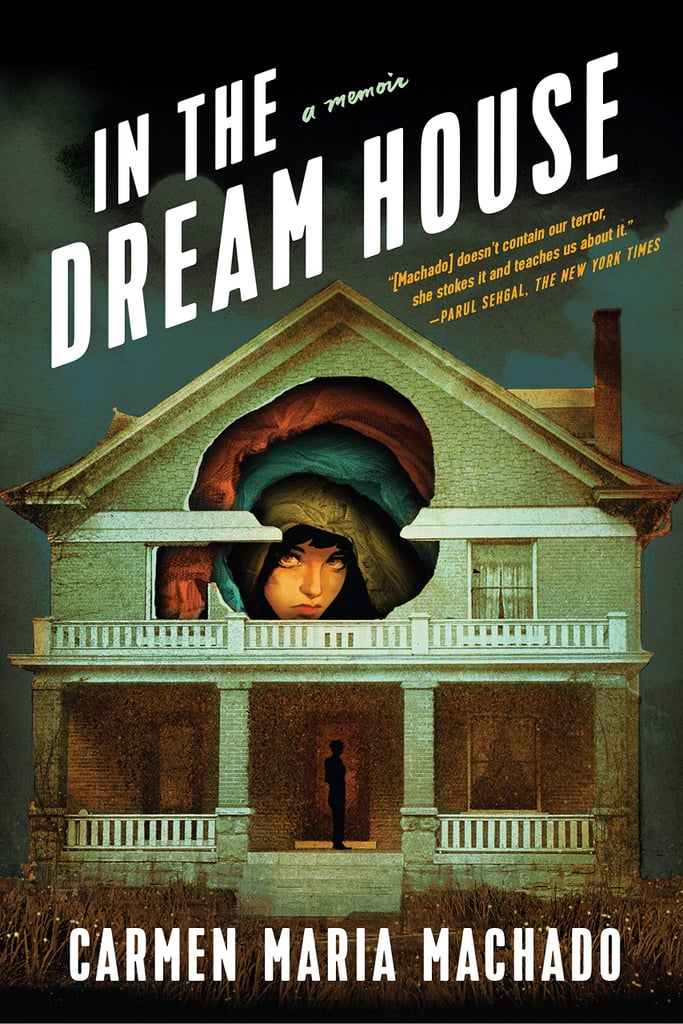

Carmen Maria Machado reads from and discusses her memoir, 'In The Dream House', at Politics and Prose.Machado’s electrifying Her Body and Other Parties—a fin. In the Dream House is Carmen Maria Machado's engrossing and wildly innovative account of a relationship gone bad, and a bold dissection of the mechanisms and cultural representations of psychological abuse. Tracing the full arc of a harrowing relationship with a charismatic but volatile woman, Machado struggles to make sense of how what happened to her shaped the person she was.

We use cookies and other technologies to customize your experience, perform analytics and deliver personalized advertising on our sites, apps and newsletters and across the Internet based on your interests. By clicking “I agree” below, you consent to the use by us and our third-party partners of cookies and data gathered from your use of our platforms. See our Privacy Policy and Third Party Partners to learn more about the use of data and your rights. You also agree to our Terms of Service.

Philadelphia writer Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House is a stunning memoir, recounting an abusive relationship with a narrative structure that provides a variety of lenses for the world that shaped her and cultural representations of abuse and queer identity. She reinvents what memoir can be.

This is Machado’s second book, following her acclaimed short-story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, which won the Shirley Jackson Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2017. Machado’s originality, alongside her mastery at bending genre into haunting, psychologically realistic, and riveting prose are present in both books. But in her memoir, Machado presents in fragments the arc of a traumatic relationship. In each chapter (some only a sentence long), she invites the reader to deconstruct these fragments’ meaning within the context of a specific narrative trope or genre. Chapter titles such as “Dream House as Stoner Comedy” and “Dream House as Unreliable Narrator” demonstrate how her experience cannot be confined to one category.

Addressing a younger self

Machado meets her unnamed girlfriend, who has “white-blonde hair” and “a raspy voice that sounds like a wheelbarrow being dragged over stones,” in Iowa City, where Machado resides while earning an MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The attraction is immediate and intense. “Your female crushes were always floating past you, out of reach, but she touches your arm and looks directly at you and you feel like a child buying something with her own money for the first time.”

Most of the book is written in the second person, which heightens the suspense and also reveals the dramatic tension between the author’s present self as she addresses her younger self. This unusual perspective further immerses the reader into the story and each chapter feels like a new room that we are introduced to during a terrifying tour of this “Dream House.” The literal “Dream House” that Machado refers to in the book is in Bloomington, Indiana, where her girlfriend lives and where Machado spends a considerable amount of time.

Before she left

In The Dreamhouse Barbie

Machado astutely captures and dissects the nuances over the course of the relationship as her girlfriend’s behavior becomes increasingly abusive. Gradually, the house and the girlfriend become fused in a miasma that threatens to emotionally destroy Machado, but she assures us early on in the book that eventually she “left, and then lived: moved to the East Coast, wrote a book, moved in with a beautiful woman, got married, bought a rambling Victorian in Philadelphia.” But before reaching this “fairy-tale ending” Machado reveals a harrowing account of what happened.

At one point, after berating Machado for not responding to a text right away, her girlfriend tells her she’s “not allowed to write about this,” and in a threatening manner, orders Machado not to. The real story becomes the predicament of writing her story. She writes, “To find desire, love, everyday joy without men’s accompanying bullshit is a pretty decent working definition of paradise.” But by admitting that her relationship does not fit into the “fantasy” of female queerness, she is faced with the dilemma of how to tell her story when it shatters the picturesque and might even bring negative attention to a marginalized community that is still fighting for basic human rights.

Speaking into the silence

Who Is The Woman In The Dreamhouse Machado

With a keenly self-aware tone, Machado addresses the “archival silence” surrounding domestic abuse within queer communities. She writes, “We deserve to have our wrongdoing represented as much as our heroism, because when we refuse wrongdoing as a possibility for a group of people, we refuse their humanity.”

In The Dream House Book Carmen Maria Machado

By heroically telling her story and illustrating through extensive research the lack of historical representation of abuse in queer relationships, she is creating a space for more stories to be told and explored. Machado writes, “I speak into the silence. I toss the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.”

Life In The Dreamhouse

♦